KL, MY

7:30:00 AM

KL, MY

7:30:00 AM

A clear technical guide to Bitcoin inscriptions: Taproot, commit-reveal, data size, validity, and a full regtest coding example.

December 8, 2025

10 min read

While Bitcoin was originally designed simply as a peer-to-peer value transfer system, recent developments have enabled a very different use-case: embedding arbitrary data into single satoshis (the smallest unit of Bitcoin). This is possible via the combination of the so-called Ordinal Theory and the protocol layer mechanism called inscriptions.

Ordinal Theory (popularised by Casey Rodarmor) assigns a unique serial number to each satoshi based on the order in which it was mined and subsequently transferred.

Ordinals themselves don’t change Bitcoin’s consensus rules or the fungibility of sats at the protocol level — they’re a social layer layer. They simply provide a way to identify and track individual satoshis.

Inscriptions are the mechanism by which arbitrary data (text, images, audio, etc.) is embedded on-chain into a satoshi. The data is stored in the witness/script path of a transaction output (thanks to Taproot and witness-discount mechanics) so that once inscribed, the data is immutable and tied to that satoshi.

AlstonChan/bitcoin-inscriptionsBitcoin inscriptions follow a two-phase process—the commit phase and the reveal phase—to embed arbitrary data into a satoshi. This often confuses most people at first, so let’s walk through what these phases actually mean.

When you inscribe something, you first send bitcoin to a specially-constructed address. This initial transaction:

So if the transaction has no data, how does the receiving address know what you want to inscribe?

Because the address itself encodes the inscription, not the transaction.

That’s the key insight.

The address you send bitcoin to is not standard. It is:

In both cases, the script contains the inscription envelope.

This script is hashed → the hash becomes your address → you fund that address.

Nothing is revealed yet because Bitcoin only stores hashes of scripts, not the script itself.

This is why:

The inscription data is embedded directly into the script with an OP_FALSE / OP_IF no-op branch:

OP_FALSEOP_IF OP_PUSH "ord" OP_PUSH 1 OP_PUSH "text/plain;charset=utf-8" OP_PUSH 0 OP_PUSH "Hello, world!"OP_ENDIFA few important points:

OP_FALSE ensures the OP_IF branch never executesAt this stage, the inscription is hidden and committed, but not yet on-chain.

To finalize the inscription, the special address needs to spend its UTXO.

Spending via the script path forces the script to be revealed. The full script (including the inscription envelope) is placed in the witness stack.

This reveal transaction includes, inside the witness:

This is the moment the inscription is visible on-chain.

After reveal, Ordinals Theory determines which satoshi in the input/output flow receives the inscription.

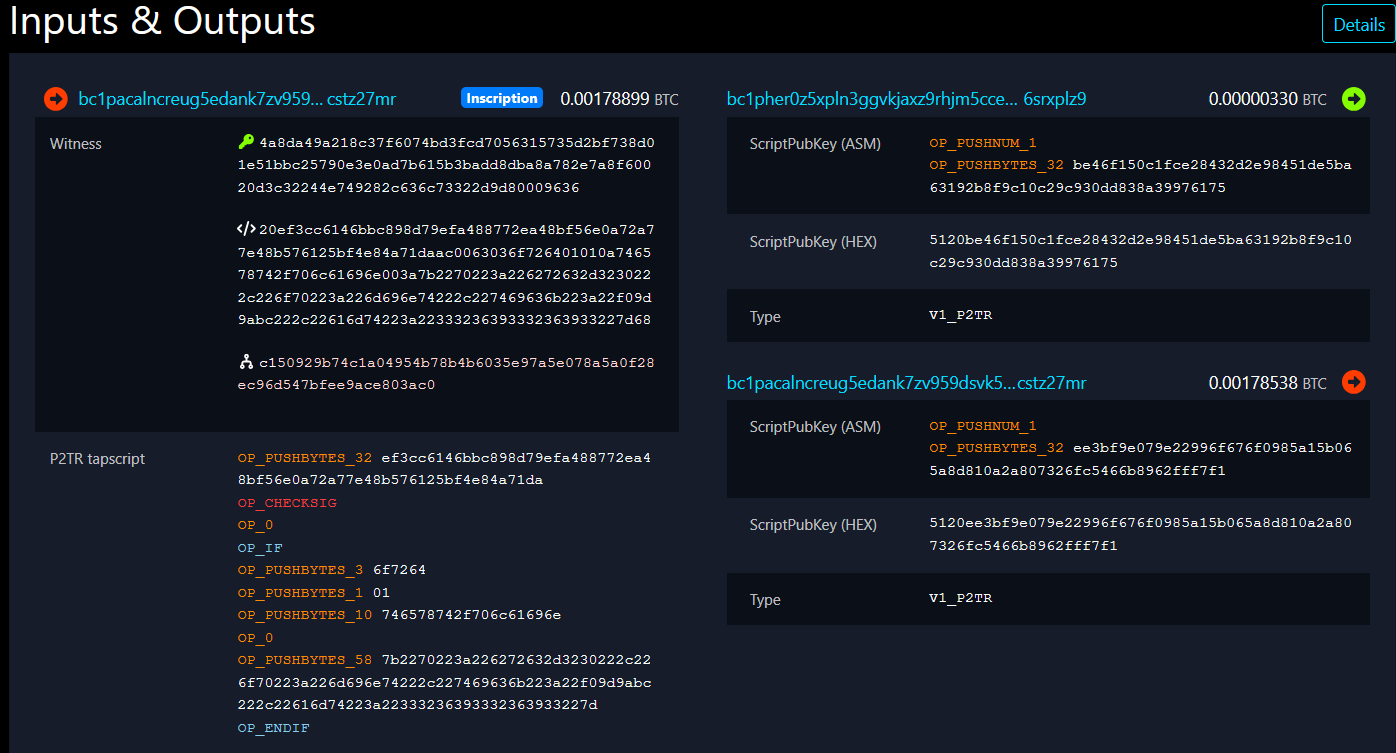

I randomly pick an example from mempool.space to show the input/output structure of a reveal transaction:

Because:

Different inscriptions produce different scripts → different addresses for the same private key.

So each inscription address:

This is normal and expected.

That’s how all inscriptions work.

If you’d like to see a complete, fully working Taproot commit-reveal inscription flow — including:

You can explore the repository here:

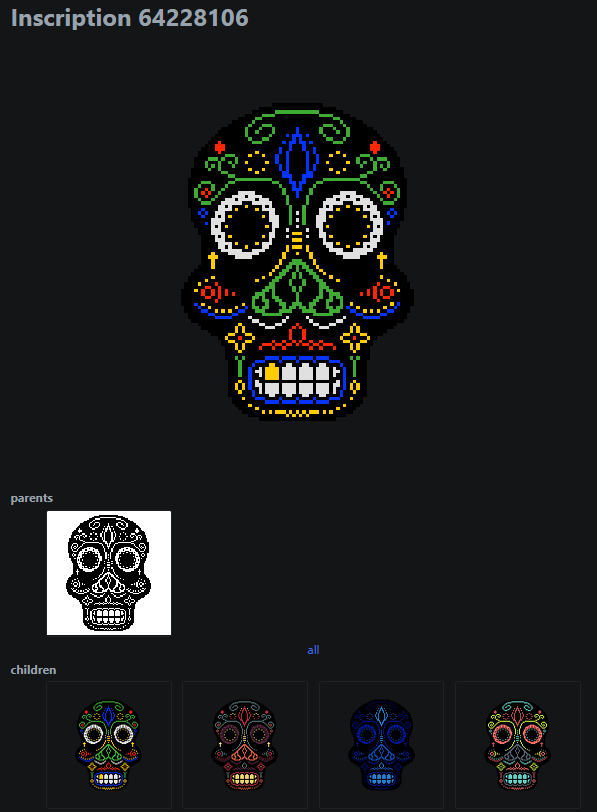

AlstonChan/bitcoin-inscriptionsOrdinals provenance is used to express parent ↔ child relationships between inscriptions (like a collection). You create a parent→child link by embedding the parent reveal TXID (encoded little-endian) into the child reveal transaction and by proving ownership of the parent UTXO in that same transaction.

Key points and the required transaction layout:

Linking: To declare that inscription B is a child of inscription A, include the reveal TXID of A (little-endian) inside the child reveal transaction. Indexers read that pointer and interpret the relationship. Example: parent_txid_reveal → little-endian bytes pushed into the child script.

Forgery protection (why anyone can’t just fake a link): If the child transaction only contains a raw parent TXID, anyone could paste any TXID and fraudulently claim a link. Ordinals conventions therefore require the child reveal tx to also spend the parent inscription’s UTXO (or otherwise prove ownership). That is, the reveal tx must include the parent UTXO as an input so the indexer can verify the spend relationship.

Practical tx layout (minimum): child reveal txs that establish provenance typically have at least two inputs and two outputs:

vin[0] — the parent inscription UTXO (spent to prove you control the parent).

vout[0] — the corresponding output that continues the parent inscription or returns its satoshi (keeps pointer semantics).

vin[1] — a new funding input used to create the child inscription.

vout[1] — the child inscription output (the one whose script will be revealed and contain the child envelope and the little-endian parent TXID pointer).

The ordering matters: indexers expect the parent spend/return to occupy the first vin/vout slots so they can deterministically identify which satoshi counts as the parent and which satoshi receives the child.

Indexers enforce the convention when resolving provenance. If you omit the parent UTXO proof or place the pointer in the wrong position, the link will be ignored or the child may be treated as standalone.

Example flow: To make B a child of A:

This pattern allows building collections (A → B, A → C, A → D, …) while preventing arbitrary parties from claiming parentage without proving control of the parent UTXO (Example transaction).

You can significantly reduce reveal transaction size by compressing your inscription data with Brotli before encoding it as hex inside the script.

How it works:

Important notes:

brotli. This tells indexers and browsers to decompress the data before rendering.This is currently the most effective way to reduce inscription costs.

No — Ordinals are not part of the Bitcoin protocol or any BIP standard.

This has several implications:

The inscription data:

Ordinal indexers (like ord) apply their own social rules to track which satoshi “carries” an inscription. This tracking is entirely off-chain logic, not part of Bitcoin’s consensus.

In other words:

Your wallet sees ordinary sats (wallet that don’t supports ordinals inscription). The Ordinals indexer sees digital artifacts. Bitcoin doesn’t care either way.

This distinction is important for understanding why inscriptions are a layer on top of Bitcoin, not a native feature of Bitcoin itself.

Bitcoin inscriptions may look mysterious at first, but the underlying mechanism is simple once you understand Taproot:

Everything else in the ecosystem—from marketplaces to provenance standards—is simply a social layer built on top of these three fundamental primitives.

AlstonChan/bitcoin-inscriptions